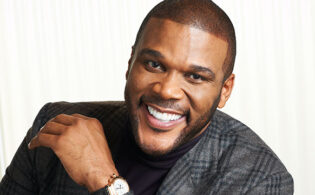

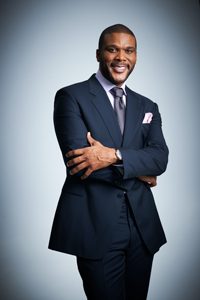

Not many writers can isolate themselves for two weeks and emerge with a completed movie screenplay or scripts for a full season of a TV series. Tyler Perry can. Raised in poverty and with an abusive father, Perry found a lifesaving escape in writing. He wrote plays and then movies, which he also directed—most featuring the hilarious, foul-mouthed, pot-smoking, gun-carrying grandma Madea, who Perry played himself. He then began writing TV series that garnered loyal audiences, and in 2017, he signed a multiyear content deal with Viacom for television, film and short-form video. Last year, he inaugurated the new Tyler Perry Studios, built on the site of Fort McPherson in Atlanta. Perry dedicated 12 soundstages to African American Hollywood legends. It did not escape the attendees of the star-studded event that a Black man born in poverty now owned the facility that Confederate forces used to advance slavery.

Not many writers can isolate themselves for two weeks and emerge with a completed movie screenplay or scripts for a full season of a TV series. Tyler Perry can. Raised in poverty and with an abusive father, Perry found a lifesaving escape in writing. He wrote plays and then movies, which he also directed—most featuring the hilarious, foul-mouthed, pot-smoking, gun-carrying grandma Madea, who Perry played himself. He then began writing TV series that garnered loyal audiences, and in 2017, he signed a multiyear content deal with Viacom for television, film and short-form video. Last year, he inaugurated the new Tyler Perry Studios, built on the site of Fort McPherson in Atlanta. Perry dedicated 12 soundstages to African American Hollywood legends. It did not escape the attendees of the star-studded event that a Black man born in poverty now owned the facility that Confederate forces used to advance slavery.

Perry is the recipient of the 2020 World Screen Trendsetter Award, in partnership with MIPCOM. He talks to World Screen about his work, the quarantine bubble model that has enabled him to restart production amid COVID-19, and television’s power to entertain and enlighten in these challenging times.

WS: When and why did you start writing, and when did you realize you wanted to work in the entertainment business?

PERRY: I started writing after I watched Oprah [Winfrey] on TV one day say it was cathartic to write things down. That was my catalyst for writing, and I wrote my first play. It was freeing to get things out of me and onto paper and to have that work. That was my beginning; that’s where it all started. There were people who saw that first play, and it inspired them and motivated them. That’s what made me want to continue with it.

WS: I’ve read that when you write, whether it’s a TV series or a movie, you write for two weeks straight and get it done. Is that true? How did you develop that discipline?

PERRY: For me, you have to understand, it was born out of a very traumatic childhood. I can go inside my imagination and create worlds and stay there for hours. That’s where this gift to be able to do this so quickly comes from. I lock my mind into a theme, and when I’m done, it’s the end of the day, and I’ve got 60 pages. It was born out of trauma and I don’t think it’s something that I necessarily crafted. It just was there.

WS: Do you have a preference for working in theater, film or television?

PERRY: I don’t. They all have their own place in my mind. There are so many sides of my brain that need to be watered and satisfied. Theater has its place. Film has its place. Running a studio has its place. I need all sides of my brain working on all those things.

WS: Has your work as an actor informed your work as a writer and director, and vice versa? Do they all feed off of one another?

PERRY: They all feed off of one another. When I do films like Gone Girl, and Those Who Wish Me Dead for Taylor Sheridan, those kinds of roles fulfill the actor in me. But he’s the part of me that needs the least attention, if that makes sense.

WS: What is the part that needs the most attention?

PERRY: I think it’s the person who is running the studio and having all of this to manage. That is very, very important—I know that sounds weird—to the one side of my brain that needs to have that attention. It needs to feed on that.

WS: Tell us about the studio. Give us a bit of the history of the facility: how you bought it, and the significance of you being there now.

PERRY: [The studio is now in a structure that] was built in the 1800s. It was a former Confederate army base. I bought it about five years ago and started converting it. I knew it was a Confederate army base. I knew the history of what that meant, but in the time we are in today, with all that is going on, it has even more significance. To have a Black man own a large piece of land in the city of Atlanta that was used as a home base to strategize to keep Black people enslaved—for me to own that now, that speaks volumes.

WS: If you weren’t the first, you were among the very first studios to restart production in the U.S. in the time of COVID-19. You went through extensive preparation to come up with the safety protocols. How did you get ready?

PERRY: A person who worked for me—he was on the set of another movie in March or April, when it started to hit in the U.S., contracted it and died. We all knew him. The crew knew him, we knew him well, so I knew this virus was serious and much more of an issue than people were letting on. I had to come up with a plan that would allow me to sequester [people] and keep them safe. I had to come up with a housing situation and bring some 360 people into a camp and make sure they were all safe. That was the biggest objective—the safety of everyone while we were working. To have two shows that have filmed their entire seasons, and have that work, has been beyond a blessing.

WS: You use a quarantine bubble for your productions. How does that work? And how do people come in if they don’t live in Atlanta, because transportation is a problem, too, isn’t it?

PERRY: Yes, if they are not in Atlanta, everybody is flown in on private [planes]. They are tested [for COVID-19] two weeks before and asked to sequester in their hometowns. Then they are tested before they get on the plane, and once they land, they are tested again and self-isolate in their rooms until the results come back. Once cleared inside the bubble, then they are tested every four days during production. What I have found is that masks and face shields actually work, and work well, to prevent the spread. Having testing is key in order to be able to do this—not only testing, but accurate testing that can get you results very quickly. We’ve been doing the PCR test on everyone, which is the most accurate. That speaks to being able to set up camp where there are no positive cases inside. All the actors were on board. The crew was on board. I’ve been working with some of these crew members for 15 years now, and they’re just amazing people.

WS: And so far, how many shows have you shot?

PERRY: Sistas and The Oval have both been shot. Those are the top two shows for BET. [I’ve also finished] shooting Ruthless and Bruh, which are the number one and number two shows on the BET+ streaming service.

WS: You have a deal with ViacomCBS, don’t you?

PERRY: Yes, and it’s been more than I could have ever imagined. Scott Mills [the president of BET Networks] and Bob Bakish [the president and CEO of ViacomCBS] have been incredible partners to work with.

WS: Are you discovering efficiencies at any point in the production process that you think might continue after the pandemic is over?

PERRY: We’ve always been streamlined, and we’ve always been about getting things done quickly and making it work, so no, there is nothing here that is different that I would keep. My crew is smaller, which can be stressful for people who need more help. But I allow them a lot more time to make their moves. Moves that would have taken 10 minutes to get to the next location are taking 30 or 35 minutes, and I’m OK with that in this situation.

WS: Are you limiting locations, which is what some producers in Europe are doing to simplify production, or are you shooting the way you have it in the script?

PERRY: I’m shooting the way I have it in the script. You have to understand that everything is written for what I have here at the studio. We’re inside these 330 acres. Every set is already here. I don’t write anything that would cause us to have to leave.

WS: Once the health and safety protocols are in place, is it more or less business as usual? Or are you doing extra things to keep everyone’s morale up?

PERRY: It feels like a summer camp! Everyone has their own rooms, and they are like hotel rooms. I have movies on the lawn. And I have church on the lawn on Sundays. We have little music festivals out there, and we have food trucks—everything you need. It’s like being in your own safe Coachella or something! [Laughs] Without the drugs!

WS: Earlier, you mentioned the state of the U.S. today. There’s the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement that has spread far beyond the U.S. and the country’s reckoning with systemic racism and economic inequality. Do you feel that films or television can play a role in fostering understanding, introducing viewers to different ways of thinking or lifestyles, or maybe even healing?

PERRY: For sure, that’s the power of film. That’s the power of television. That’s the power of our industry. We get to paint pictures and tell stories, and the most powerful stories are the ones that leave you different. I look at people like Ava DuVernay, who has done some amazing work that speaks on so many levels. Even when I think about some of the stuff I have done, I just tried to make people laugh and feel good, but also give them something to think about. It’s a medium that is so important in change.

WS: How did Tyler Perry’s Young Dylan come about?

PERRY: That was Brian Robbins, who was at Paramount and is now running Nickelodeon. He called and said, “Listen, I found this kid, Dylan Gilmer. We’ve got to do something with him.” We put the show together, and it worked very well. My son loves it. I’m just excited for those kids.

WS: If television can change hearts and minds, is it especially important in children’s programming to feature the world the way it is? At what age do you start telling children the truth about the world?

PERRY: I’m struggling right now with a 5-year-old who will be 6 in November. I’m going to have this conversation about race with him. But the beauty about where he is now is that he is unaware of it. As long as I can hold [back] that conversation from him, I’m willing to do so. It’s very important that people are shown how they are, as they are, to everyone, so that it’s not like it was when I was growing up that everything that was beautiful was blue-eyed and blond. And everybody who was on television was blond or white. It was very rare to see a Black person on television in my very early years. Then it got a little better into the mid-to-late ’70s, and I started to see more and more of us. It’s just important that we see people as we are.

WS: I’ve found that children retain that innocence until middle school unless they come from toxic families. The prejudice seems to kick in after middle school. But 6 is a beautiful age. Do you love seeing the world through your son’s eyes?

PERRY: For sure, it’s so beautiful. It’s so pure. He talks about all his friends at school and never mentions them by race.

WS: I’m lucky I have a job, a roof over my head and food in my fridge, but I’ve had difficult moments during these past months. Your book Higher Is Waiting has been a great deal of help. Is it fair to say you are a hopeful person, and your spirituality helps you? How do you see the future?

PERRY: Thank you for saying that. I appreciate that. I have to be hopeful. Given where I come from and what I’ve endured, if I didn’t have the hope of a better day, I wouldn’t be here—if I didn’t have the prayers of my mother, or if my mother didn’t take me to church, and I didn’t hear the pastors and the choirs singing of hope and joy, even in the middle of our despair and darkness. That is where [the hope] came from. And it’s a light that cannot be destroyed. That hope will always burn in me.